Coigach Series 10. Oil on 10×10″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

More painting progress of the Coigach series, with the continuing challenge of saying less with more simple brushwork – trying to hone in on the essentials of what makes a particular landscape speak to me. Here’s the series so far …

-

-

‘Coigach 1’. Oil on 5×7″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 5’. Oil on 5×7″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 2’. Oil on 5×7″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 3’. Oil on 5×7″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 4’. Oil on 5×7″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 6’. Oil on 10×10″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 7’. Oil on 10×10″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 8’. Oil on 10×10″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 9’. Oil on 10×10″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

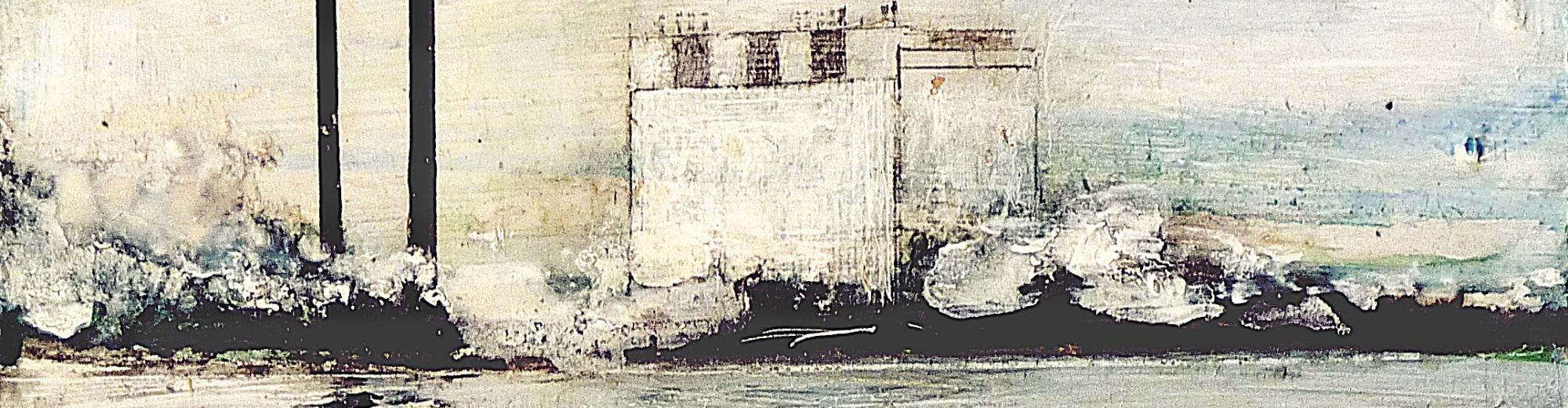

‘Coigach 10’. Oil on 10×10″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

-

-

‘Coigach 11’. Oil on 10×4″ wood. Rose Strang 2023

I’ve been visiting the Coigach area for decades because several of my dad’s friends live there. As is often the way – one family member moves there, others follow, then eventually people become intergrated with the local community, making friends, or finding long term partners.

Coigach means ‘five’ in Gaelic, and it refers to the five townships or villages of the area, the main one being Achiltibuie (I love that name and wish I knew what it meant!) Near our friends’ house there’s a broch down near the sea – a form of dwelling, or maybe fort dating from the iron-age – incredibly strong and sophisticated structures architecturally.

This particular one is a bit crumbled down (there are almost intact ones in Orkney and, interestingly, very similar structures in Sardinia) but still impressive given its age. This wild area has obviously been peopled since the retreat of the ice-age, like the rest of Scotland’s north west coast. It’s unexpected to the new visitor since this seems one of the most remote corners of the world, but if you remember that the sea and rivers were the highways back then, not land, it makes sense.

I’ve stayed in various places, one time on Tanera Mor, one of the Summer Isles of the coast of Coigach. This was the island where cult film classic The Wicker Man was made. I’m never sure if it’s a cult film because it’s a bit hilarious, or because of its atmosphere – both, no doubt. The island was indeed somewhat spooky, or at least I found it so, on a dark rainy day wandering across the boggy moorland with my friends, exploring caves in the black cliffs, aware we were the only people on the island at that time.

More convivial are the times spent on the mainland of Coigach with family friends. I remember some legendary Ceilidhs – lots of dancing and serious whisky drinking, people here really know how to party, including the local police, I’ll say no more about that though, and it was in the mid 1990’s so nothing to do with anyone there now!

One of the most unusual evenings I experienced was on one of the smaller Summer Isles, a new owner had just bought the island and he appeared to have transported his entire suburban house with fluffy wall-to-wall carpets, massive hi fi system, leather-effect sofas, canaries in cages and obligatory conservatory, to an amazing spot overlooking a majestic loch (his was the only house on the island). Towards midnight we were all dancing to Rod Stewart’s Do ya think I’m sexy? then a piper led us outside into the cold night air and started to play his bagpipes – it was an affecting moment after all the party noise. We all fell silent as the notes echoed across the loch, they seemed to carry for miles.

One new year as we travelled back to Edinburgh, my dad’s car started to fail as we traversed Glen Coe and Rannoch Moor. It’s not a good place to feel the car beging to sputter and die. We all sat tensely, driving at a snail’s pace along the icy road, towering mountains above and vast white moors stretching ahead. I think there was maybe one house that may or may not have been inhabited as we drove along. Finally we got to a garage – a huge relief.

People mean a lot in areas like Coigach, it’s a lifestyle you can’t take lightly since money alone doesn’t help when you’re snowed in, or your boat breaks down. I have many enjoyable memories of this place, not least recently when we stayed there briefly with friends after our wedding in May. No matter the time of year the colours always seem to me alternately moody and wet then sparkling, dazzling sunhine, rarely anything in-between. I love driving along in the car over the winding roads down from the wet mountains and bleak moors, down past little cottages nestled in the tall grass and towards the summer isles dotted across a sparkling sea. I’ll attempt that subject soon …